— BIM in architecture

Gravida proin loreto of Lorem Ipsum. Proin qual de suis erestopius summ.

Recent Posts

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria.

— BIM in architecture

For many architects and professionals working with BIM, these initials represent an “advanced” working method, making it possible to integrate and handle a new set of processes based on the major cultural shift we are currently experiencing in the way we design, build and, above all, inhabit. However, for others, BIM is simply the promise of a considerable improvement in the management of procedures and the exchange of information, geared towards the economic and financial aspects of production and management within the AEC industry.

Clearly, BIM can be understood and used in one or both of these ways. However, it is important to bear in mind (i) that from either of these viewpoints, the need for a new approach and understanding of the design process, supported by digital information and representation, communication and production systems is not going away; (ii) that the phenomenon is international, and therefore the “Pandora’s box” of new and different approaches is open, with BIM, rather than a definitive solution, representing a dynamic starting point for redefining rules, methods, objectives and management and evaluation processes, something which other methodologies have, to date, been unable to do, and, finally, (iii) that it has rapidly become clear that this marks the end of one project cycle and an entirely new approach to the role of the architect as we know it today. We are thus confronted with a change in the professional activity of today’s architect, whose designs no longer focus solely on the construction. All evidence suggests that they are, instead, beginning to incorporate the operation of the building, with a focus on managing the architecture and built spaces produced as a result of designs, and ensuring their future management, evaluation and ongoing capacity for use and adaptation.

This being the case, the viewpoint which initially associated BIM with the simple ambition to develop more and “better” designs, achieving “better” results, from a point of view more closely aligned with exact sciences than with the arts (of which architecture is one), and focusing on a rigorous but rather unarchitectural concept of systematization and a constant search for objectivity, in order to produce “better” buildings, may be reductive. This view is, in other words, the idea that BIM methodology can be used to optimize, improve profitability, and, to an extent, homogenize architectural output, which has traditionally been varied, with little systematic focus on economic results and more closely associated with phenomenological, social and cultural aspects which support and legitimize its creation as a mirror of civilization- as the will of an epoch translated into space (Mies Van Der Rohe) which many have difficulty understanding:

“Never talk to a client about architecture. Talk to him about his children. That is simply good politics. He will not understand what you have to say about architecture most of the time. An architect of ability should be able to tell a client what he wants. Most of the time a client never knows what he wants.” (Ludwig Mies van der Rohe)

The use of BIM in architecture will not be viewed as a tendency towards specialization and the structuration of universal methods in order to create an output which also tends towards the “universality” of modern man, an outdated universal previously held, promoted and implemented in architecture with results which were, at times, rather undignified and unassertive. The thirst for universals and the constant search for an absolute truth and perfect method can sometimes lead to stagnation and an urgent need for reflection within the discipline.

Having been put forward by several authors as the future of architecture, BIM cannot be treated as just another challenge. Its seems impossible to dissociate it from the real world context, these volatile times of constantly shifting social relationships and needs, and the emergence of the concept of happiness which cannot be defined by patterns, norms or stable paradigms.

It is against perpetually turbulent backdrop that humans realize themselves and architecture is constructed, aiming not to establish fixed rules at a given moment, nor to allow itself to be bound by material, technological or philosophical limitations. This is how it was in the past, how it is in the present and how, we believe, it will be in the future, given the intrinsic connection and overlapping of Architecture and Life.

3D project for Abuja office building, Nigeria, 2016

Frank Lloyd Wright put it best when he said, “Architecture is life, or at least it is life itself taking form and therefore it is the truest record of life as it was lived in the world yesterday, as it is lived today or ever will be lived.” From this point of view, efforts to achieve ideals of specialization are rather unnatural in the process of architectural development, “An expert is a man who has stopped thinking. Why should he think? He is an expert” (Frank Lloyd Wright). It follows that the constant challenge in architecture lies in thinking, in the intelligent search for solutions, and not simply in output and the supporting construction work.

From the technological point of view, setting aside the idea of dangerous specialization intrinsic to any methodology, it is possible to view a strategy based on the methods which BIM promises to bring to Architectural design, as representing an opportunity for new ways of working, to which architects must remain open. The capacity to control temporal phasing and levels of development and to perform digital visualization and simulation trials, as well as the ability to work collaboratively on the design, are among the competitive advantages favouring easy adoption of the methodology in new practices, architectural and design firms.

The capacity to integrate new content, data, information and knowledge into the project design, as well as managing the great and ever increasing need for information through the creation and handling of digital models, in order to construct a virtual representation of the design containing all associated data is, in fact, a driving factor in the acceptance and increased use of BIM in the varied, unique and methodologically non-standardized processes which each architect uses to construct their own Architecture, their unique vision and their place in the World.

Meanwhile, this methodology also facilitates and encourages collaborative work on projects, something which architects have always sought to stimulate and establish in one way or another. In light of the increasing level of complexity involved in producing the Design, and the consequent demands on construction, BIM has become a tool for ensuring that design and management processes are able to meet requirements. By providing the increasing number of actors, suppliers and partners involved in the process with easy and secure access to information, we facilitate collaborative working processes, reducing risks and conflicts, in order to objectively improve, if not the quality of Architecture, then the quality and suitability of the working process associated with architectural design, providing conditions in which many formal and procedural aspects of the design can be better controlled.

Therefore, the main reasons for the success of BIM in some architecture practices today can be deemed to reside in its capacity to bring us closer to the dream of total control over a design, and in its ability to preview and simulate construction work virtually. By doing so, we can master many aspects of construction, avoiding or foreseeing the surprises which occur in many of the related tasks, thus minimizing risks and conflicts and making it possible to resolve these before they even arise.

In this particular approach, in which BIM is linked to aspects of the project monitoring process, we can see how a model developed and designed using 3D tools becomes a very powerful instrument, perfectly suited to the three-dimensional and spatial design methods architects use to solve problems- which is the very essence of design. BIM can, therefore, be considered to offer both methodological continuity and an opportunity to improve cost-effectiveness, through the use of a model which enables us to extract various forms of information and data, fundamental to the critical reviews carried out during the design process. It is, therefore, dynamic and rarely understood as a finished product, as there are constant opportunities to improve, increase and facilitate communication between specialists, clients, and contractors, by means of visualization and a dynamic and integrated 3D design.

Furthermore, once the major issue of interoperability, which is still impaired by many software houses in their quest for hegemony, has been resolved, the ability to work in a collaborative environment on a design shared between the different disciplines, is a promising indicator of a new approach, in which information sharing is encouraged and carried out in a new way.

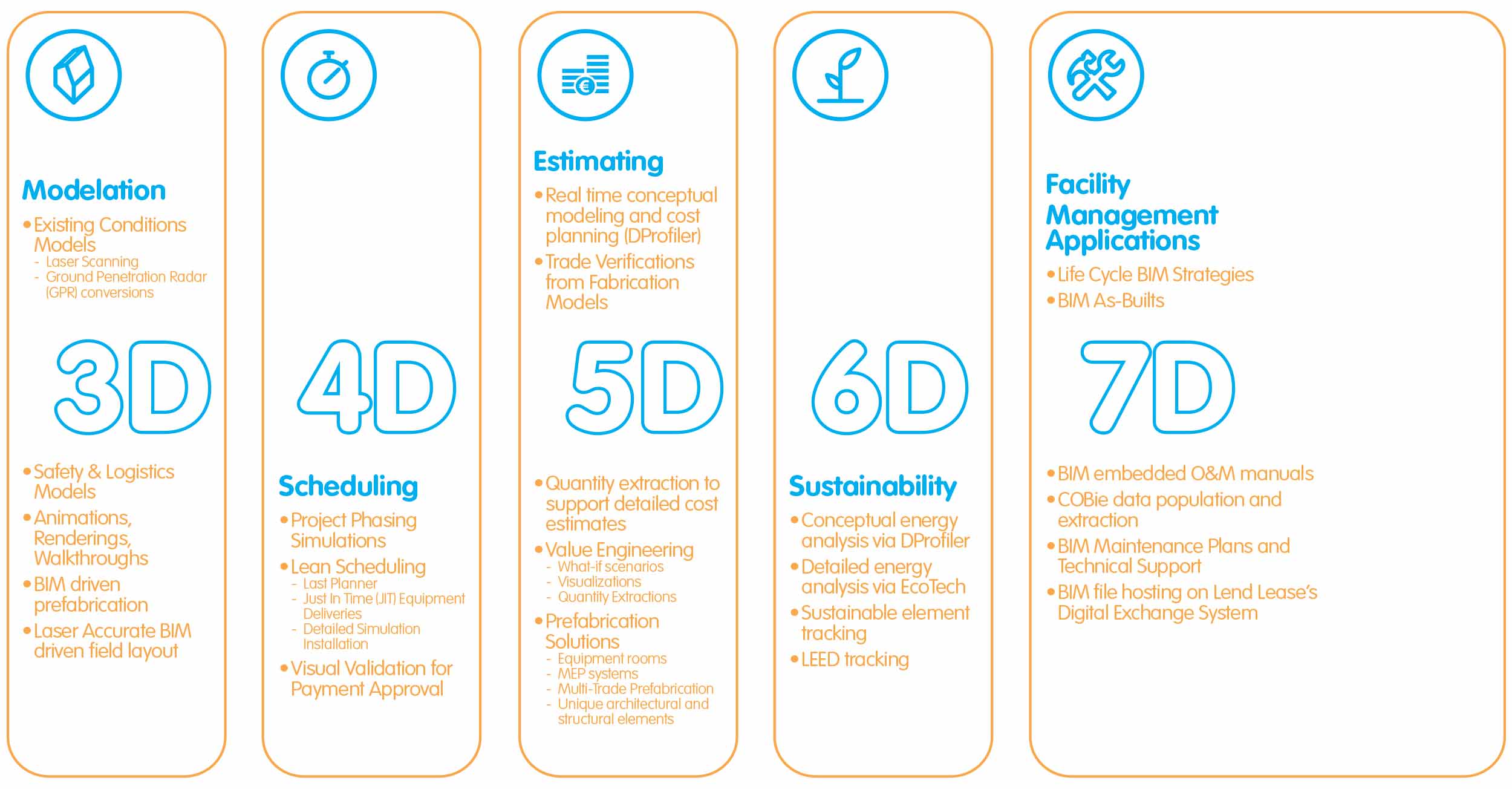

The ease of handling and understanding construction and management systems and processes, made possible by integrated 3D models, encourages the development of BIM projects which include 4D, 5D, 6D and 7D management processes. These give the architect, designing and managing via their model, all sorts of information which goes beyond their usual insight into the design. In light of these new possibilities, extra attention must be paid to guaranteeing not only the traditional authorship of the design drawings and/or model but, more importantly, the management and integrity of data, developing strategies for updating the model (and not only the design), through effective communication and, above all, working to enable ongoing monitoring of the operation and maintenance of the building constructed.

Axonometric view for Abuja office building, Nigeria, 2016

In this respect, the establishment of general rules governing the lifespan of a model and the associated data and information (BIM), its use, collection and ownership, in addition to the specifications developed by the Industry Foundation Class (IFC)- connecting software developers to intelligent building standards (BuildingSmart) in order to manage and maintain open building and construction models (OpenBIM) – are all issues which young architects must remember, take on board and participate in, in order to assume an active role in the long process of digitizing design, construction and Architecture, which affects us all.

The idea that it will soon be possible to develop a design using any software and simply choosing a sharing environment or platform, regardless of the program used, is already becoming a reality in the development of models containing highly detailed information, yet which have experienced no information loss or interoperability issues. Here, the application of BIM in design will become increasingly realized.

Given that a design is not completed when works begin and the architect’s involvement increasingly extends into other areas of work, the development of designs using 3D models makes it possible to follow up and monitor building progress, documenting and recording decisions made and their variants. This facilitates the resolution of problems related to the design, the building and its future usage, maintenance, adaptation and final demolition.

In parallel, the ease of producing, correcting and updating designs thanks to the increasing availability of digital methods, brought about by mobile technology, makes it possible to visualise, include, verify and validate models and alternative solutions closely interlinked with the digital models developed, in which the use of virtual and augmented reality may become a real asset in improving understanding and, above all, increasing the chances of architectural plans being implemented.

Virtual construction of a project before its physical construction, digital trials, and the production and management of data regarding the building lifecycles, made possible by linking digital models to databases containing project information, offer a wide range of advantages and possibilities in terms of Architectural design. These, together with careful planning and the necessary coordination between the various specialisms working on the BIM model, bring a new perspective, and new demands, to the traditional understanding of the way architects will practice in the future.

“Something interesting is happening” – a world of opportunities in which virtual, digital, simulation and immersion combine with the constant integration of information, through the construction of a memory, a process record, an integrated archive, a database- which contains, and offers visualizations of, every aspect of a design. In this environment of constant creation and simulation, all those involved can find, create and read detailed technical information on processes, designs and construction systems. It is fair to say that BIM, while perhaps not be the revolution expected, is increasingly becoming the herald of this ideal of innovation in our approach to designing and building, and will continue to be intelligently applied to architectural practice, without erasing what came before in terms of doing and thinking Architecture.

More than a specialism, BIM’s use in architecture can be understood as an opportunity to improve and develop working processes and tools. Rather than offering or promising an unwanted miracle solution, BIM impacts on processes and alters the mentalities of those involved. For this reason, we ought not to confuse BIM integration with the simple idea of information technology and software, training and instruction, or with the mere replacement of programs which specialize in a single field, rather than the inclusive, all-encompassing perspective integral to architectural practice.

This change to working processes must, necessarily, drive young architects to master new fields, develop new skills and, above all, gain new types of knowledge and, perhaps as a result of this, develop and achieve different perspectives, different forms – different Architectures, emerging from the intersection of new and old approaches to the discipline, through a process which society has validated, and therefore built.

While the current climate proves that it is necessary to understand and promote the need for change, it will remain difficult to put this into practice, and to locate it within the ongoing conflict between the will to build the future and the persistent desire to preserve and respect the past.

Nuno Lacerda Lopes

in BIM IS MORE MAGAZINE #01, 2016, Porto

Something interesting is happening.

3D render view for Abuja office building, Nigeria, 2016