— why BIM?

Gravida proin loreto of Lorem Ipsum. Proin qual de suis erestopius summ.

Recent Posts

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria.

— why BIM?

On the subject of Housing, Adolf Loos, Austrian architect considered by many authors to be a fundamental defender of the ideal of modernity, expressed in an architecture free from all excess ornamentation said, “The house is conservative”. According to Loos, housing is intolerant to change and its evolution is slow, and impeded by the constant search for consensus.

In housing, and the way in which we design, build and inhabit it, architecture- as a mirror of the socioeconomic and cultural processes of its specific historical context- has a faithful portrait of the different states of development and the diverse processes of evolution and regression which humankind demands when building its world.

Technological improvements, in their many forms, have, however, brought about significant advances worthy of our consideration, firstly, in construction processes; then in the development of ideas about usage and their integration into these processes; and, more recently, in the process of designing, simulating and assessing planned buildings or spaces.

The use of digital processes to support architectural design has made it possible to develop new approaches, some of which break with conservatism, representing a kind of “revolution”. It is perhaps for this reason that in the early days of their implementation, results were described as a curiosity or an experiment and were, at times and in certain schools, considered not to be truly “architectural”. In other words, they did not result from the canonical process for discovering a form or creating an architectural object by directly applying the Vitruvian triad of Firmitas, Utilitas and Venustas.

In a way, this stereotype illustrates how architecture has, at certain times, distanced itself from other disciplines essential to its realization and justification. However, today’s reality has brought about a series of changes which have led us to accept that something interesting is happening to the world in which we live.

Tom Goodwin, strategy, marketing and innovation consultant, goes further when he brings us face to face with this new reality, saying, “Uber, the world’s largest taxi company, owns no vehicles. Facebook, the world’s most popular media owner, creates no content. Alibaba, the most valuable retailer, has no inventory. And Airbnb, the world’s largest accommodation provider, owns no real estate. Something interesting is happening!”

By situating the world of architecture, engineering and construction against this backdrop of profound change, we must consequently accept that this world is also changing and, most importantly, offering major changes to the way in which we design, build and inhabit new and old architecture: this is the architecture of our times.

It is true that of all their wide-ranging and diverse professional, cultural and civic actions, the architect’s greatest role has been establishing relationships. Pedro Ramalho refers to this state of being within the profession, and to staying relevant and objective as an architect, saying, “Being an architect implies an attitude to life and to society which is, in principal, incompatible with piecemeal or aesthetic analysis, which is either solely technocratic or, conversely, solely theoretical-ideological. (…) Each one of us is an architect in our own way and this architectural being is the result of a personal story, ongoing praxis and a considerable dose of theoretical, ideological, sociological, etc. meditation; it is a culture, with all of the totality that this word implies. To disrupt this totality, analytically shattering the dynamic and indestructible synthesis we represent, is to risk impoverishment, a risk which is, however, made essential by any explanation.” (Pedro Ramalho, 1980).

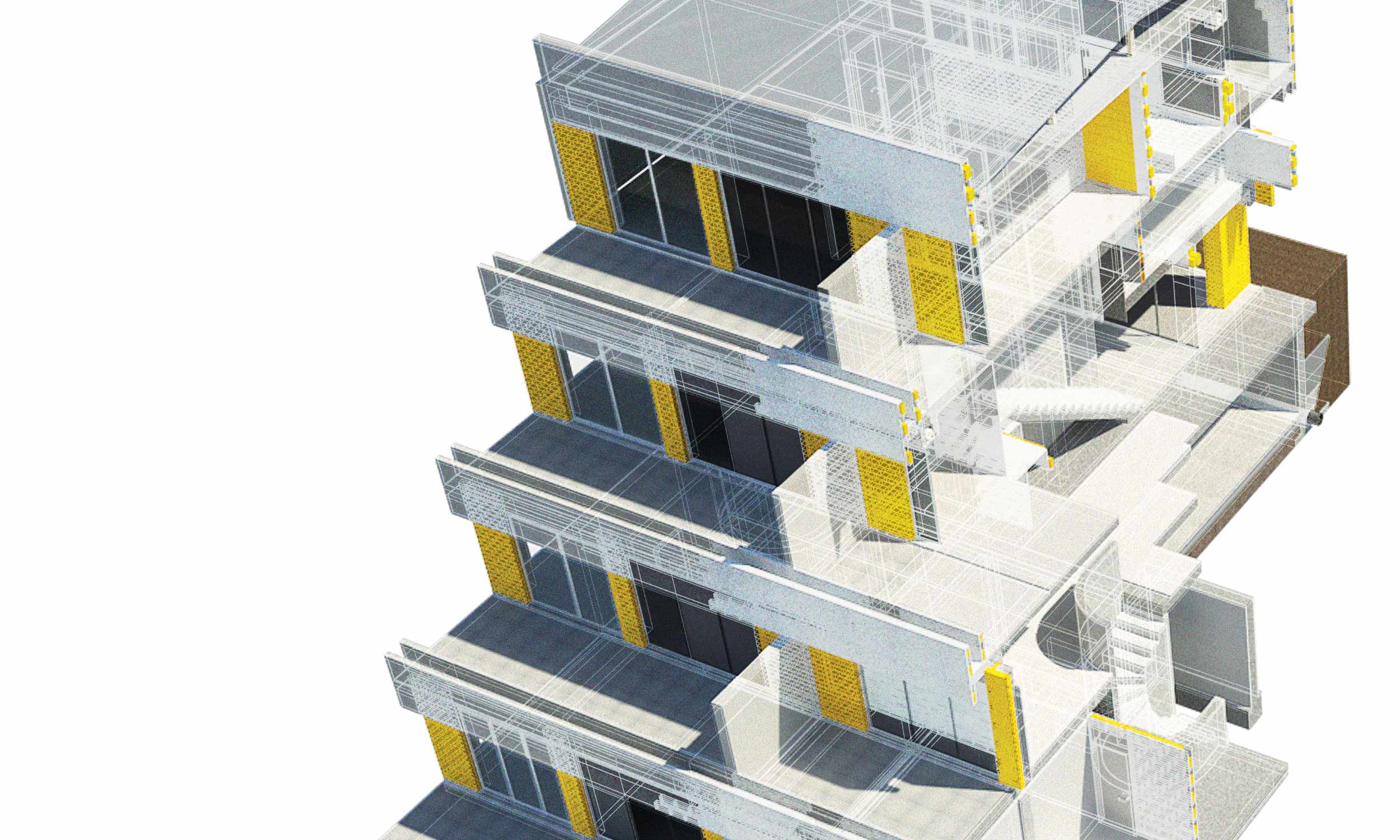

3D project for Moinho de Vento dwelling complex, VNGaia, 1994

We can understand the digitization of the design and architectural process as a trend-driven tool for the exchange of information between various partners, authors, designers and producers of the content which shapes and defines the design for construction of a building, piece of infrastructure or urban facility.

Nuno Lacerda Lopes

This, perhaps, explains the difficulty or slowness in adopting new practices and new planning and design methods based on approaches which tend towards compartmentalization, and adhere to strictly technical analysis methods, technocratic by their nature and therefore posing the risk of distancing us from the necessary critical, ideological, sociological and civic analysis of the whole, on which architecture is traditionally founded.

Viewed in this light, the process of digitization of architecture, from design to construction, can lead, (if the world has not already transformed), to alienation and distancing from the necessary all-encompassing viewpoint which the discipline has always championed.

We uphold the longstanding and widely accepted belief that new working tools- the “digital world”, computer graphics, design and representation tools associated with new ways of planning and visualizing- are transforming the construction industry and, necessarily and perhaps as a result of this transformation, the fields of architecture, engineering and management. These industries embarked on an initially slow, but increasingly necessary and now indispensable, adoption of digital representation, communication and calculation methods, and the virtualization of processes, design decisions and implementation schedules.

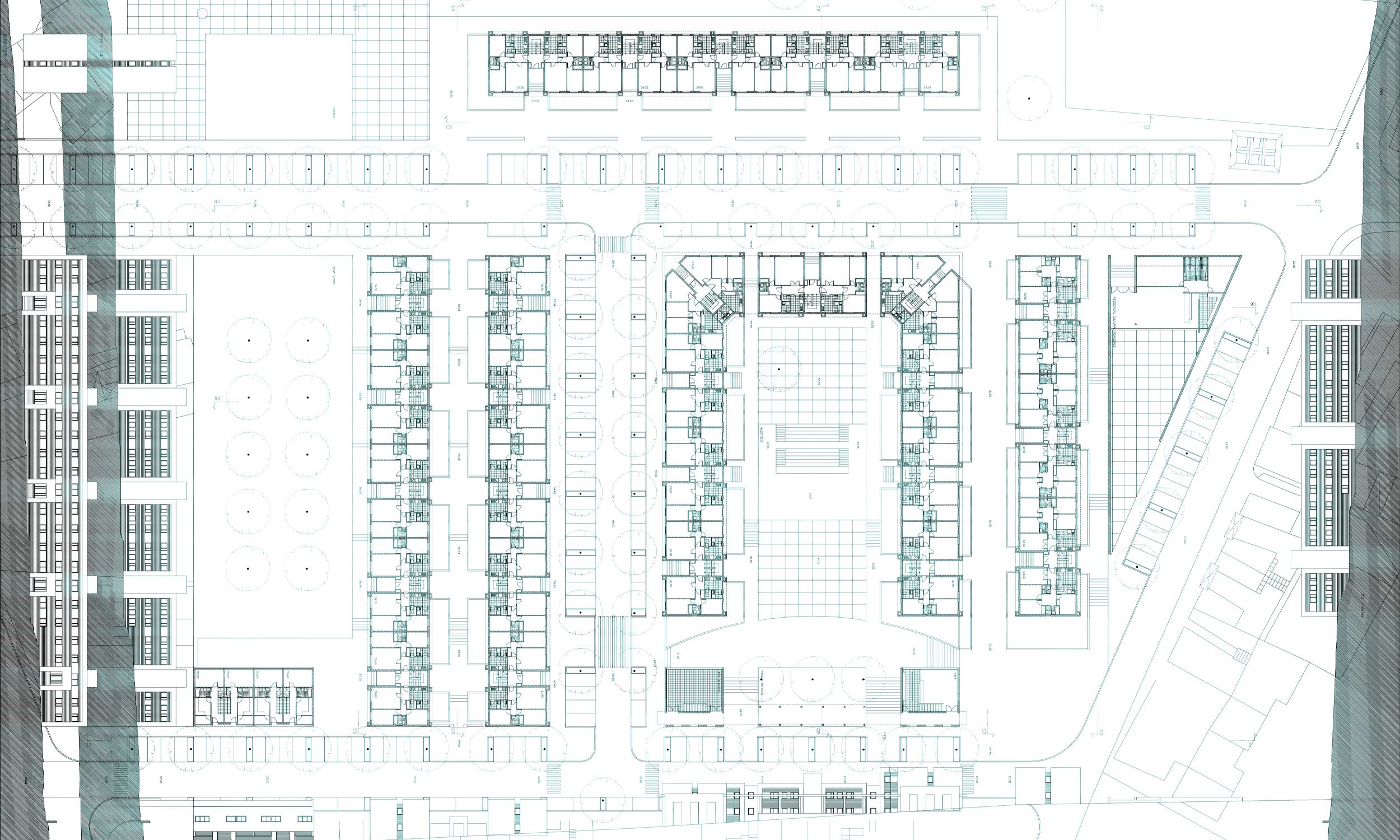

Quinta de Paramos social housing complex, Espinho, 1995

Paradoxically, despite the countless advantages of digitizing processes- some of which simplify means of communication and clarify project coordination and management- the process of changing mentalities proved to be a slow one, associated, first and foremost, with the realization that digital design processes enabled architects, designers and engineers to work faster and seemingly more efficiently, while potentially saving money.

It is fair to say that architects took some time to accept this revolution initiated by engineers passionate about the new challenges of computing, the development of calculation algorithms and, above all, mental and intellectual openness to increasingly widely accepted automatic calculation programs which were spreading, from one floppy disk to another, and sometimes suffered from a lack of critical analysis in evaluating results, leading to them being followed blindly.

More cautious, and perhaps reactionary, architecture attempted- and still attempts to this day- to maintain as close a link as possible with a traditional design and production process, in which manual drawings, sketches and trial and error representations, at times, represent a particular ideal of production and an adherence to a certain way of designing and doing architecture- belonging to a School.

The time factor therefore became another aspect of this growing disquiet. A working method based on doubt and examination of alternatives seems to be at odds with the pertinence of the decision and the methodological concept that in architecture, the opposite is also true (Távora, 1982). This idea, which highlights an awareness of the changeability of circumstances was, however, something which engineers did not consider acknowledging, let alone understanding.

However, as time went by, the dissemination of new technologies which, little by little, began to appear in the offices of engineers and architects, made the idea of sharing and integration increasingly possible. Even without a framework for ensuring compatibility, the increasing possibility and ease of developing collaborative projects, and the need to coordinate plans in order to keep pace with transformation and change in the labour market, became evident.

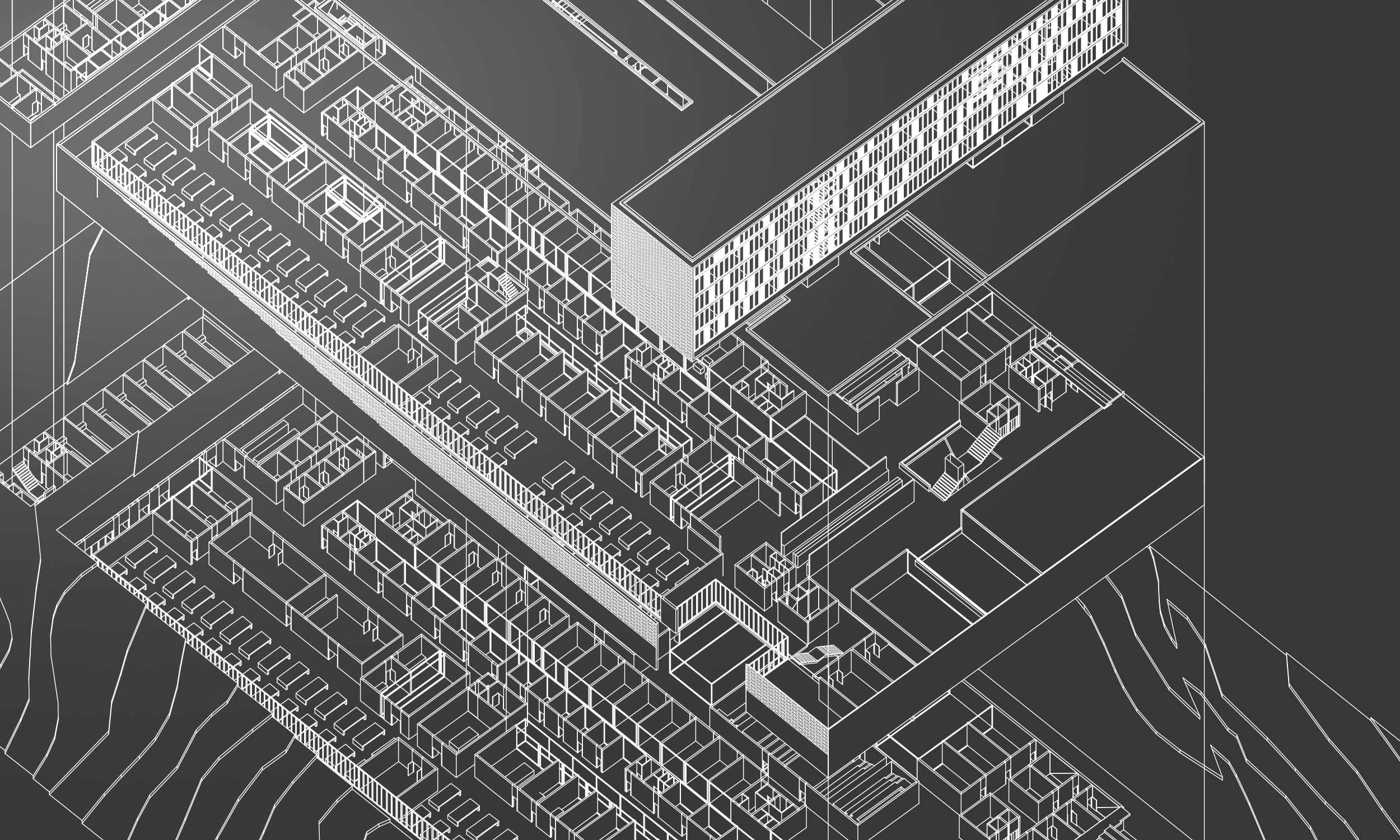

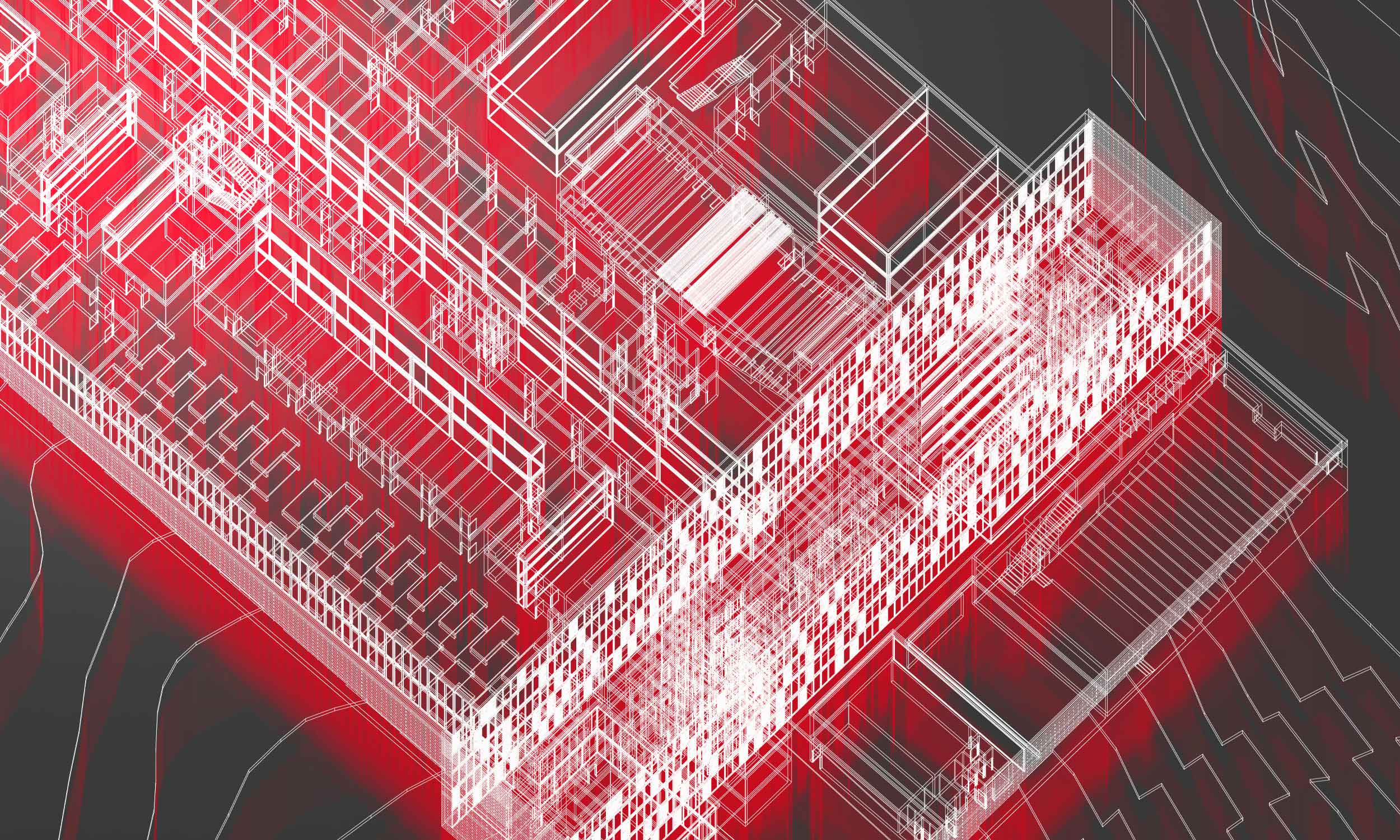

Axonometric view for Medical Sciences Building, Universidade do Minho, Braga, 2000

With this in mind, we can understand the digitization of the design and architectural process as a trend-driven tool for the exchange of information between various partners, authors, designers and producers of the content which shapes and defines the design for construction of a building, piece of infrastructure or urban facility.

While the languages used by the various disciplines were structurally different, it was the need for common ground which led to the development of hegemonic positions within the programming houses. These were split between those which adopted processes closely linked to the architectural approach, those which adopted the utilitarian standpoint of the engineers, and others with a distinct, all-encompassing view of the process, calling for innovation and integration of procedures from fields such as the aeronautical and automobile industries, the production of parts and mouldings, as well as the space and military sectors.

Initially, the use of digital project development methods in small and medium practices was, above all, viewed as a means of facilitating the integration of different designs, offering new, easier, and more accessible data sharing, and adding a new unifying element to the design method and process, unaltered by Computer Aided Design, establishing only the need/obligation to define a common language. This led to the standardization and adoption of representation and calculation systems, at times uncritically. The main value of these lay in extending digital design practices to other professionals and facilitating new project analysis, preparation and implementation procedures, thus moving toward the ideal of a shared goal which the virtualization of architecture promised.

However, Portuguese architecture resisted, and continues to resist this change to procedures, developed at times by the “School of Design” embodied by Siza, a methodology essentially based on manual drawing, combined with the sense of synthesis which architecture constantly seeks and which, in Siza’s particular case, is superbly evident in his beautiful sketches, the trademark starting point from which all of his designs develop and transform a concept into unique and unexpected works of architecture.

The increasing attention garnered by his unique body of work which, more than design, is the fruit of his capacity for critical analysis and integrating the context, exceptions and problems arising in each project, may have led to the confusion of a whole generation of architects who took a part as the whole story, slow to take on board, learn and develop new design practices, and afraid of creating new architectural forms. It may be that the fundamentalist views of some of his followers delayed the progress and implementation of digital and virtual planning practices, as evidenced by the fact that these are non-compulsory in academic and university settings, and that their adoption and use in architecture, which had become an untouchable “Sacred Cow”, can bring with it the risk of negative repercussions.

However, not settling on any reductive vision of the process, Siza insists on the need for contrast, comprehensiveness and the need to incorporate into the design and representation process any tool capable of providing clarity or enabling greater mastery of the design, in order to enhance our understanding of architectural phenomena, including scale, light, the environment, construction materials and systems, space and the wide range of fields involved at each stage of the design process, in no particular order and without prior definition or taxonomy. This is, despite it all, made possible by the virtual domain.

“If there were no problems and contradictions to resolve, I would never have another idea”, said Álvaro Siza in a 1989 interview, stating, on the subject of the architect’s specialist knowledge, that the latter, “does not know, and does not need to know, anything at all. We cannot, simultaneously, be specialists in structures, acoustics, energy, construction, history, sociology, in the world of aspects which make up a project. Deep down, we know nothing at all. Now, what we need to know is how to work together with a series of specialists and transform this work into a design, a clear image. (…) the Architect needs oppositions”.

This belief, and the discovery of a new, powerful and effective design and representation process therefore offer a basis for investment and research into the BIM methodology. This desire and pursuit are, as Siza stated, a result of the natural and powerful will to elucidate and master, to understand and look deeper, to experiment and innovate in the key architectural phenomena.

Nuno Lacerda Lopes

in BIM IS MORE MAGAZINE #01, 2016, Porto

If there were no problems and contradictions to resolve, I would never have another idea.

Álvaro Siza, 1989

Axonometric view for Medical Sciences Building, Universidade do Minho, Braga, 2000