ISBN

978-989-98808-6-3

Edition

CIAMH, FAUP

Year

2013

Number of pages

120

Dimension

14,5x22cm

ISBN

978-989-98808-6-3

Edition

CIAMH, FAUP

Year

2013

Number of pages

120

Dimension

14,5x22cm

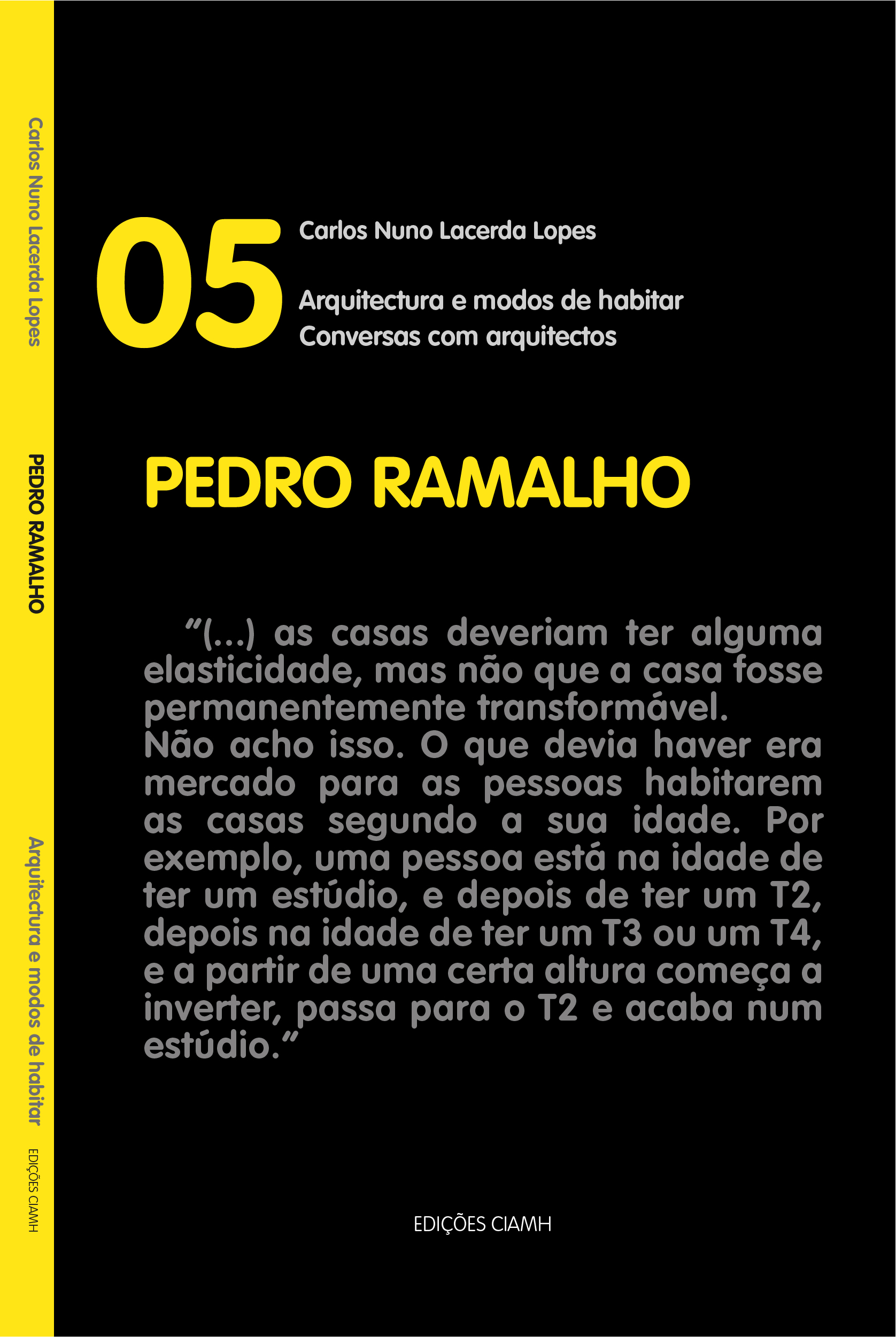

“This is a collection of interviews by architect Nuno Lacerda Lopes. They are conversations between architects of the School of Oporto where the process of building an ideal of architecture, profession, society and school is sought, based on a personal and open reflection and even clarify the theoretical and practical concerns as well as the circumstances that underlie Portuguese architecture today”.

Excerpt

“Architect and Professor Pedro Ramalho, professor at the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Oporto, one of the most renowned Portuguese architects, with remarkable experience in the field of public facilities and collective housing, among other works that he has carried out over several decades of professional practice and has contributed with great works to our best national architecture.

There are several remarkable buildings, from the Pasteleira Block, the Faculty of Engineering of the University of Oporto, the Cooperative of Sete Bicas, the set for the INH in Guimarães (among others), as well as its numerous single-family dwellings that it has designed. There are so many works, that it would not be easy to list them all. But, in any case, I would like you to tell me about your experience, this long academic and professional experience, and to revisit your dwellings, your way of understanding housing.

I would like to start by asking you, what was your education? What was your education like? What were your influences? What was the reality in Portugal? How does an architect start working?

Well, I entered the School of Fine Arts (save error in 1955) with much joy and enthusiasm. There was an authoritarian and retrograde regime in which teaching was ideologically controlled. The high school was not (at all) a nice house and when I finally entered the Fine Arts I passed to a completely different world. The relationship between teachers and students was something that seemed truly exceptional.

When I entered the school, the “old retirement”, which I attended during one school year, was still in force. Then, when the reform of 57 started, by advice of Master Carlos Ramos, I went back; it was a year that was lost, but a great hope was placed in the reform of the teaching of architecture, namely the updating of its programs. It was a difficult decision, but one that I took with enthusiasm.

Undoubtedly, the “new reform” brought a new credibility to the architecture course in pedagogical terms. Subjects which did not exist before were introduced, linked to technology but also to the reformulation of the Theory and History of Architecture.

What I think was profoundly negative was the two propaedeutic years at the Faculty of Science. At that time all university courses in science were obliged to attend, which was nothing more than a “filter” in the difficult access to higher education.

In the course of architecture it was profoundly negative and dramatic, they were real “lead” years. It was a disaster that took 10 years to repair.

For my part, the invitation that Otávio Filgueiras made to me, at the end of 57, to join the office (which I was setting up at the time with Soutinho), allowed me to do what I was really excited about. I was only enrolled for one year in the General Physics Course of the Faculty of Sciences, without going to school, but I worked in architecture (as a draftsman).

When I returned to the School I was more prepared than my colleagues which allowed me to finish the course with some ease.

I can conclude that my training between the School and the atelier, as was normal among architecture students, was good and allowed me to enter the liberal profession earlier.

When I arrived at the School (we are talking about the end of the 50’s) the architectural standards had as reference Le Corbusier and the architects of the Modern Movement. It was the rationalist school, where I pontificate Master Carlos Ramos, and the exemplary and most “visited” works were those of Losa (Rua de Ceuta, Rua de Sá da Bandeira), Loureiro (the Parnaso building) of Viana de Lima (Bloco de Costa Cabral), Mário Bonito (Bloco do Ouro), but also in Lisbon the Bloco das Águas Livres by Nuno Teotónio Pereira.

But suddenly, these references were overlaid by a new vision of architecture to which the Survey of Portuguese Architecture and the work of Fernando Távora (the Market of Vila da Feira, the house of Ofir, the primary school of Cedro) and the theoretical influence of Zevi with his challenge to the Modern Movement and the appreciation of the work of Wright and the example of Alvar Aalto.

It is what at the time was called, in a very general way, the organic movement.

For me it was a different way of making architecture, more human, less functionalist, less rigid, a new language, but above all considering the interior space as an absolute value.

This is how Alvar Aalto appears as a reference in the School and the shift towards Finland begins.

Maybe more than the study visits to Finland marked the works of Alvar Aalto in Germany. The Bremen tower, the block in Hansa in Berlin, the cultural centre of Wolfsburg”.